Glaciers Reveal Dire Warning for Water-Scarce Future

Earth's glaciers contain less water than we thought, and that's not good news, scientists say.

February 7, 2022, 11:05 am

Earth’s glaciers are melting as a result of human-driven climate change, a trend that has both local and global implications because glacial runoff provides freshwater to communities and ecosystems, while also contributing to sea level rise, which threatens coastal populations around the world.

3inches

less sea level rise from glacier melt

FIRST ATLAS OF GLACIAL MOVEMENT AND THICKNESS

Now, scientists led by Romain Millan, a postdoctoral scholar at the Institute of Environmental Geosciences in Grenoble, France, have produced the first global atlas of glacial movement and thickness, which reveals that the world’s glaciers have the potential to add an estimated 257 millimeters (10 inches) to sea level rise—roughly 20 percent less than previous estimates of about 13 inches.

A DANGER TO FRESHWATER RESOURCES

On the surface, this finding may sound like a rare piece of good news about rising

sea levels, but Millan

and his colleagues emphatically reject that characterization for a few reasons. Most importantly, the

research raises alarms about freshwater availability in regions such as the tropical Andes Mountains,

which

contain 27 percent less glacial ice than previously calculated, according to the team’s study,

which was

published on Monday in Nature Geoscience.

“The takeaway message is that we find, overall, that there is less ice in glaciers and it's bad news

in terms of freshwater resources for people around the world,” Millan said in a call.

“

There is less ice in glaciers and it's bad news in terms of freshwater resources for people around the world,”

NEW SATELLITE MAPPING TECHNOLOGY

The team built this robust map of world glaciers from more than 800,000

images of Earth from space taken

between 2017 and 2018 by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 satellites, and NASA’s

Landsat-8 satellite. This space-down view covers 98 percent of Earth’s glaciers, some of which have never

been mapped before, including regions in Caucasus, New Zealand, and islands located off the coast of

Antarctica.

The vast trove of data enabled the researchers to clock the velocity of glacial ice worldwide for the first

time, adding a key missing piece of the puzzle compared to previous estimates of global glacial volume. The

technique exposed some of the world’s fastest flowing ice, such as Penguin Glacier in Patagonia, which is

moving at more than seven miles per year.

98%

of earth's glaciers have now been mapped

“Since 2013, there has been a revolution in satellite imagery,” Millan

explained. “For example, with

Sentinel-2, you can get a picture of the same glacier every five days, which has completely changed the

way

we look at glaciers. This allows us to really do a systematic mapping of the ice velocity of all the

glaciers.”

“We mapped the ice velocity at a resolution of 50 meters” which “allows us to look at fine details in

glaciers that was not possible in the past,” he added. “The ice velocity gives you a sense of where the

ice

is thin and where the ice is thick, and knowing that, we can re-estimate the volume of the world's

glaciers.”

11%

less glacial ice in total

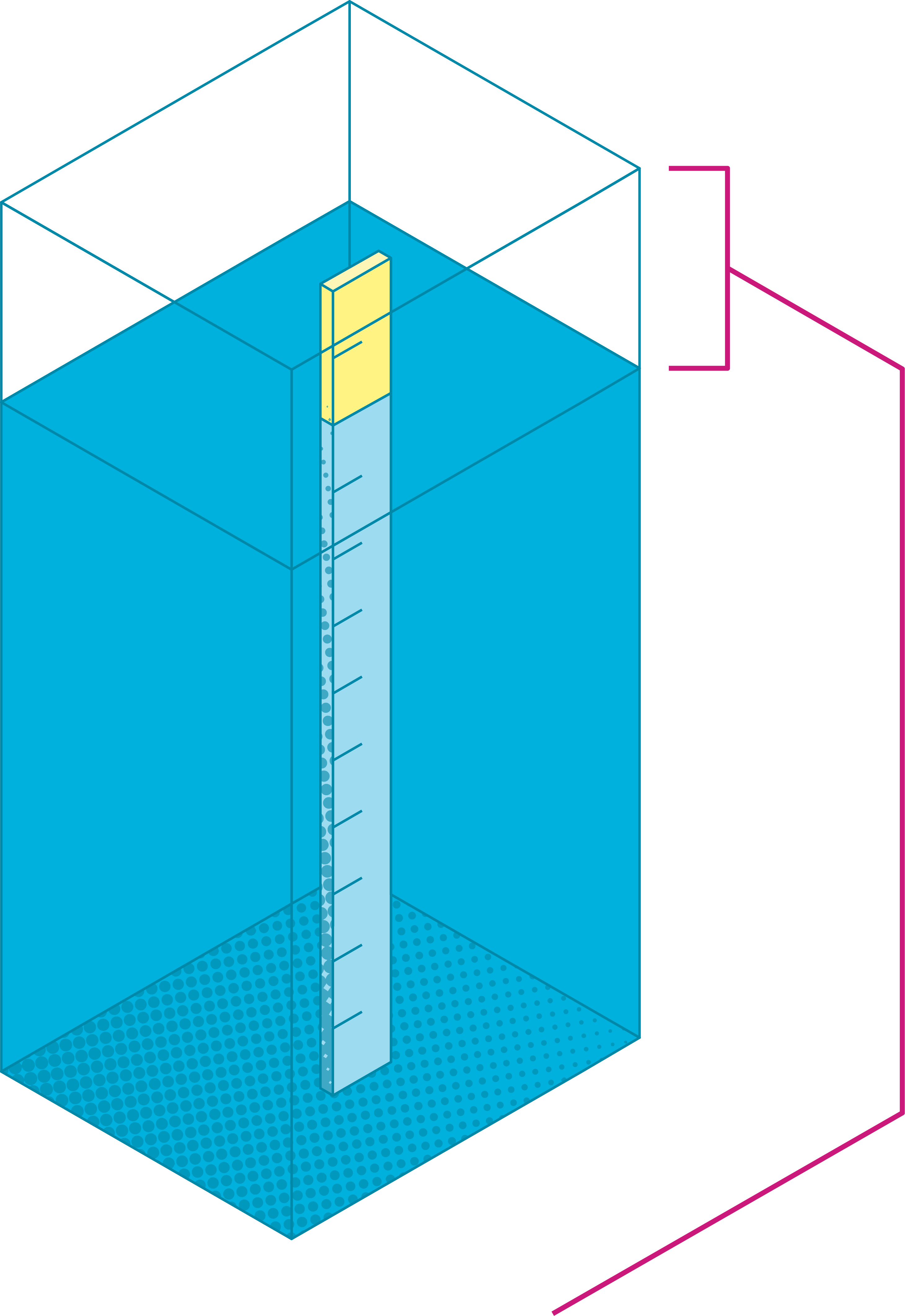

UNEVEN DISTRIBUTIONS OF GLACIAL ICE

Overall, the results revealed that the world’s glaciers contain 11 percent less

ice compared to previous

estimates, though these ice deficits were not evenly distributed across the globe. Some regions contain far

more ice reserves than previously estimated; the glaciers of the Himalayas, for instance, hold 37 percent

more ice than suggested by past studies.

However, communities in North Asia, which the team estimates may have 35 percent less ice than previously

estimated, as well as those located in parts of the Andes Mountains, may be much more vulnerable to

freshwater depletion in the future than anticipated. This finding has

implications for millions of people

who need freshwater not only to drink, but for crop irrigation and hydropower, among other

applications.

“

The loss of the massive ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica would still swamp the glacial contribution to rising sea levels by hundreds of feet in the long term.”

UNMAPPED ICE SHEETS

The new atlas can also improve projections of sea level rise, a trend that has consequences for coastal communities around the world. However, Millan noted that the study only models glaciers around the world, as opposed to massive ice sheets like those located in Greenland and Antarctica, which will be the major driver of sea level rise over the long term. While the researchers found that glaciers may contribute three fewer inches to rising sea levels, the loss of those massive ice sheets would still swamp that glacial contribution by hundreds of feet.

35%

less ice in North Asia (and 27% less ice in the Andes)

NEEDING MORE INFORMATION

Millan and his colleagues said that their findings will need to be

bolstered by field surveys of the

world’s glaciers, which will double-check the satellite observations from the ground. Even so, the study

represents a quantum leap in our understanding of global glacier cover, with major implications for

scientists in the field as well as policy-makers hoping to mitigate the effects of human-driven climate

change.

“This new geometry is more coherent in time, and captures the shape of the glaciers in a much better way,

which changes everything for the future evolution of glaciers,” Millan concluded.

35%

less ice in North Asia (and 27% less ice in the Andes)

Designed by Jocelyn Grant | WWU Digital Media

Design 2022 | Portfolio

Based on “First 'Atlas' of World Glaciers Reveals Dire Warning for Water-Scarce Future”

Published by Vice 2.7.22